Virginia General Assembly passes bill allowing localities to use ranked-choice voting in some municipal elections

On Feb. 27, the Virginia State Senate voted 22-18 to approve HB1103, which would allow local governments to implement ranked-choice voting (RCV) for select municipal elections. All of the Senate's 21 Democrats and one Republican voted in favor of the legislation. Eighteen Republicans voted against it. The same bill had passed the Virginia House of Delegates on Feb. 7 by a vote of 57-42. Fifty-four House Democrats and three Republicans voted in favor of HB1103. Forty-two Republicans voted against it (one Democratic member did not vote). HB1103 now goes to Gov. Ralph Northam (D) for his action.

If enacted, HB1103 would allow local governments to implement RCV in elections for county boards of supervisors and city councils. The state board of elections would be authorized to "promulgate regulations for the proper and efficient administration of elections determined by ranked-choice voting, including (i) procedures for tabulating votes in rounds, (ii) procedures for determining winners in elections for offices to which only one candidate is being elected and to which more than one candidate is being elected, and (iii) standards for ballots." Localities would be liable for any implementation costs incurred by the state. The Department of Planning and Budget has estimated those costs at approximately $1.3 million.

What have been the reactions?

The following is a sample of the commentary surrounding HB1103:

- Del. Sally Hudson (D), the bill's chief sponsor, said, "It’s a benefit to communities like mine in Charlottesville that tend to have very low-turnout primaries in the summer and then local elections in the fall that often have multiple candidates running for a handful of open seats. You end up with really split elections and less certainty about which candidate has majority support from the community."

- Del. Chris Runion opposed the bill, saying, "It confuses the voter, and it complicates the process. I would prefer that a voter goes in and makes his decision, casts their ballot and goes back and knows this is who they voted for and that’s who they support and they go home satisfied with that result."

- Elizabeth Melson, president of FairVote Virginia, which has advocated in favor of the bill, said, "With ranking, if a candidate meets a voter who favors an opponent, the conversation need not end; it can shift to second choices and areas of mutual concern. In places with ranked choice already implemented, candidates sometimes even campaign in groups of two or three and ask to be second or third choices. It could lead to more civilized and issue-based campaigns and less mud-slinging."

- Quentin Kidd, a professor at Christopher Newport University, said, "So if you had a city or a county that was 50-50 split, ranked-choice voting could really mix things up and make for some really healthy political competition. But in a county that’s really rural and really Republican, Democrats would almost be locked out. In a city that’s really Democratically-oriented, Republicans would almost be locked out."

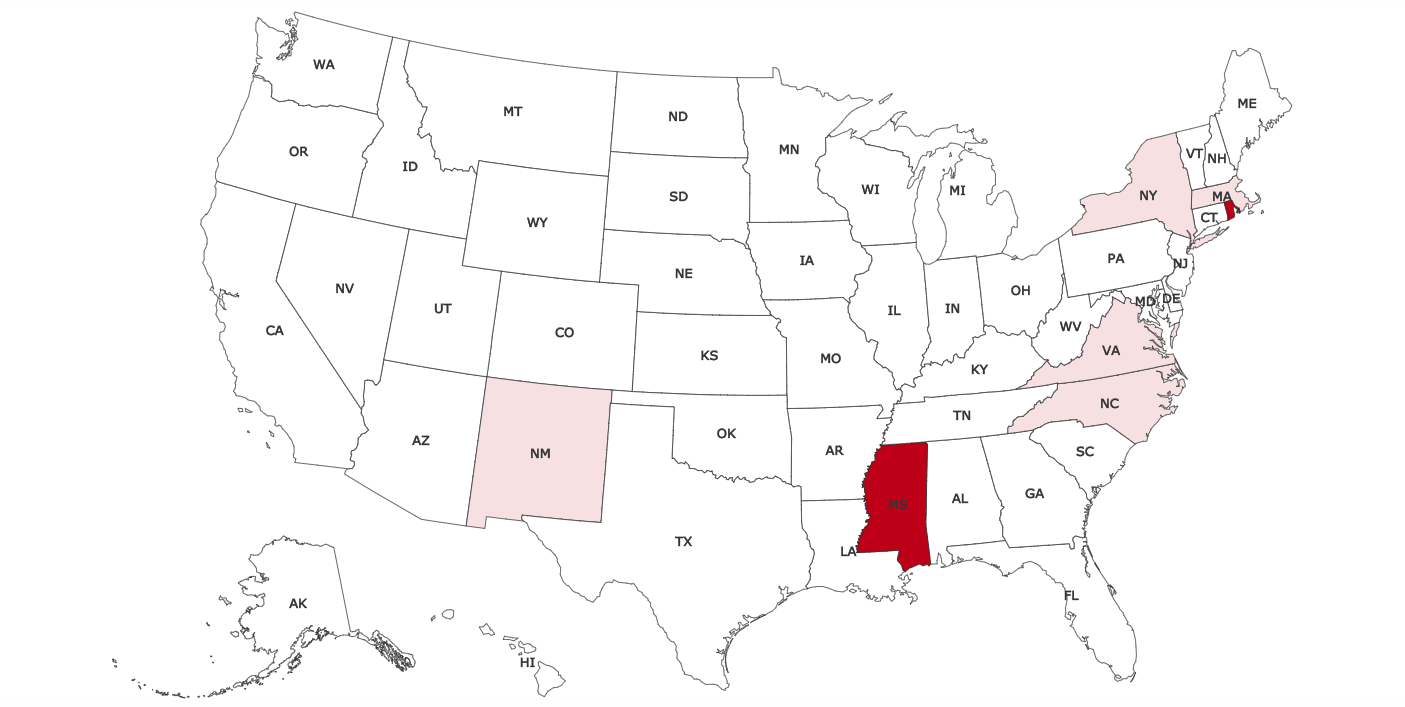

What other jurisdictions have implemented RCV?

Maine is the only state that has implemented RCV for federal and state-level elections. Nine states have jurisdictions with RCV at the local level. On the map below, these states are shaded in gold. Another four states have jurisdictions that have adopted, but have not yet implemented, RCV. These states are shaded in blue. A complete list of implementation sites is available here.

In other RCV news …

On March 3, citizens in Portland, Maine, approved a charter amendment extending the use of ranked-choice voting to all city council and school board elections. Previously, ranked-choice voting only applied to mayoral elections. The charter amendment passed with 81 percent of the vote.

Virginians to decide constitutional amendment transferring redistricting power from legislature to commission

On March 5, the Virginia House of Delegates voted 54-46 to approve a resolution placing a redistricting-related constitutional amendment on the ballot for Nov. 3, 2020. The ballot measure would transfer the authority to draft the state's congressional and legislative district plans from the Virginia General Assembly to a 16-member redistricting commission comprising eight state legislators and eight citizens.

What does the constitutional amendment propose?

Under the amendment, the commission would draft the maps and the Virginia General Assembly would vote either to approve or reject them. The Virginia General Assembly would be prohibited from amending the maps. If the Virginia General Assembly were to reject a map, the redistricting commission would draft a new one. If the second map is rejected, the state supreme court would enact a district map.

Maps would require approval by 12 of 16 (75 percent) commission members, including six of eight legislator-members and six of eight citizen-members. Leaders of the legislature's two largest political parties would select members to serve on the commission. Based on the current composition of the General Assembly, the commission's legislative members would include two Senate Democrats, two Senate Republicans, two House Democrats, and two House Republicans. The commission's eight citizen members would be recommended by legislative leaders and selected by a committee of five retired circuit court judges.

How did the amendment make it to the ballot, and what comes next?

In order to place a constitutional amendment on the ballot, a majority vote in each chamber, in two successive legislative sessions, is required. In 2019, the House and Senate, with Republican majorities, approved the amendment. Democrats won control of both legislative chambers in November 2019. This year, the Senate approved the amendment 38-2. In the House, nine Democrats and all 45 Republicans voted to advance the amendment; 46 Democrats voted against the amendment. In November, a simple majority vote is required to enact the constitutional amendment.

For more information on the support and opposition arguments on this amendment, click here.

For more information about the legislative process that put the amendment on the ballot, click here.

Are other states considering similar measures this year?

This is the first ballot measure certified for 2020 related to redistricting. Measures might also be on the ballot in Arkansas, Missouri, Nevada, Oklahoma, and Oregon. In 2018, five states — Colorado, Michigan, Missouri, Ohio, and Utah — voted on initiatives to alter redistricting procedures or establish redistricting commissions. Voters approved all of them.

Ballot access requirements for U.S. Senate candidates in 2020

Thirty-three seats in the United States Senate are up for election in 2020. How do prospective candidates get on the ballot in their respective states?

Generally speaking, a candidate must pay a filing fee, submit petition signatures, or both in order to appear on the ballot. Filing requirements vary from state to state. Filing requirements also vary according to a candidate's partisan affiliation. Candidates of the major political parties are sometimes subject to different filing requirements than unaffiliated candidates.

Petition signature requirements exist on a broad spectrum. For example, Kentucky requires partisan primary candidates to submit two petition signatures (candidates are also liable for a $500 filing fee). This petition requirement is the lowest in the nation for Senate candidates in 2020. By contrast, Texas requires unaffiliated candidates to submit 83,717 petition signatures, 1 percent of all votes cast for governor in the last election. This petition requirement is the highest in the nation.

Filing fees are similarly variable. Kansas requires unaffiliated candidates to pay a $20 administrative fee. This fee is the smallest in the nation for Senate candidates in 2020. By contrast, Arkansas Republican candidates are liable for a $20,000 filing fee, a larger filing fee than that imposed in any other state this cycle.

We have compiled complete filing requirements for major-party and unaffiliated Senate candidates in 2020. To peruse the data, click here.

Legislation tracking

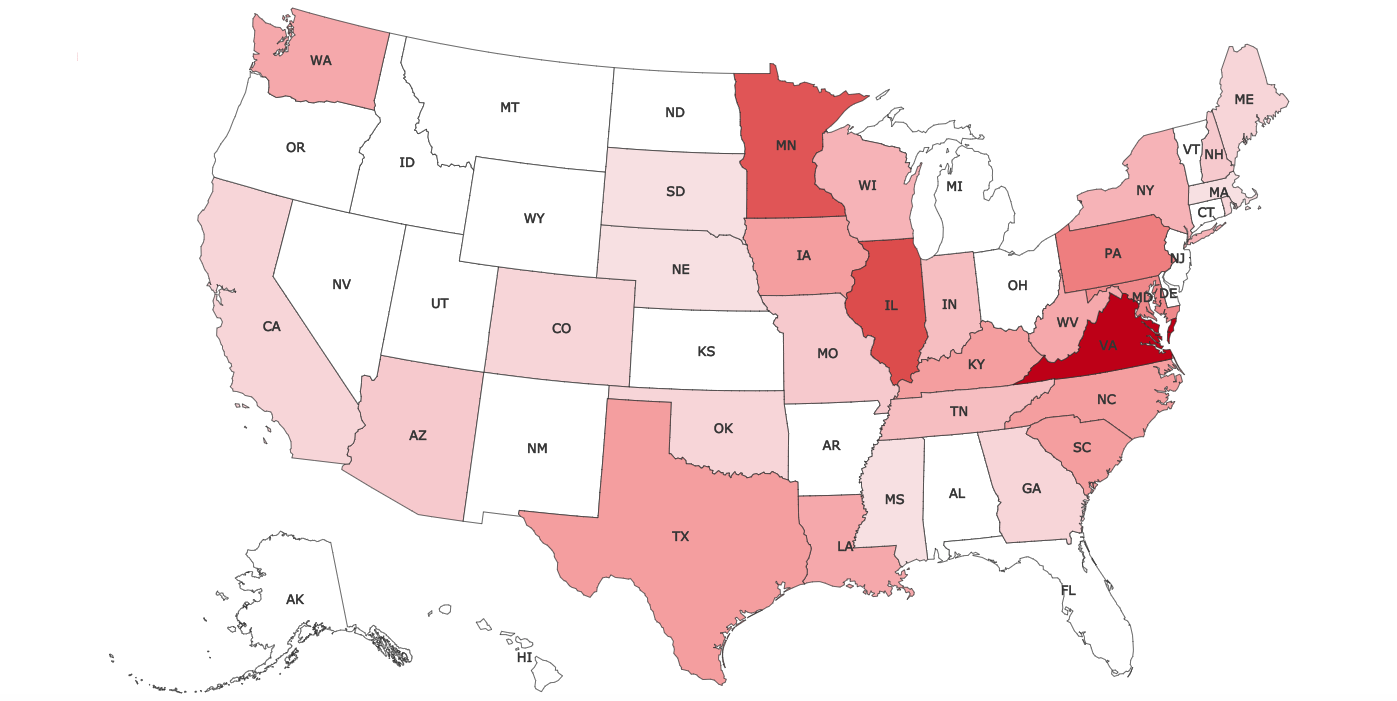

Redistricting legislation

The map below shows which states have taken up redistricting policy legislation this year. A darker shade of red indicates a greater number of relevant bills.

Redistricting legislation in the United States, 2020

Current as of March 9, 2020

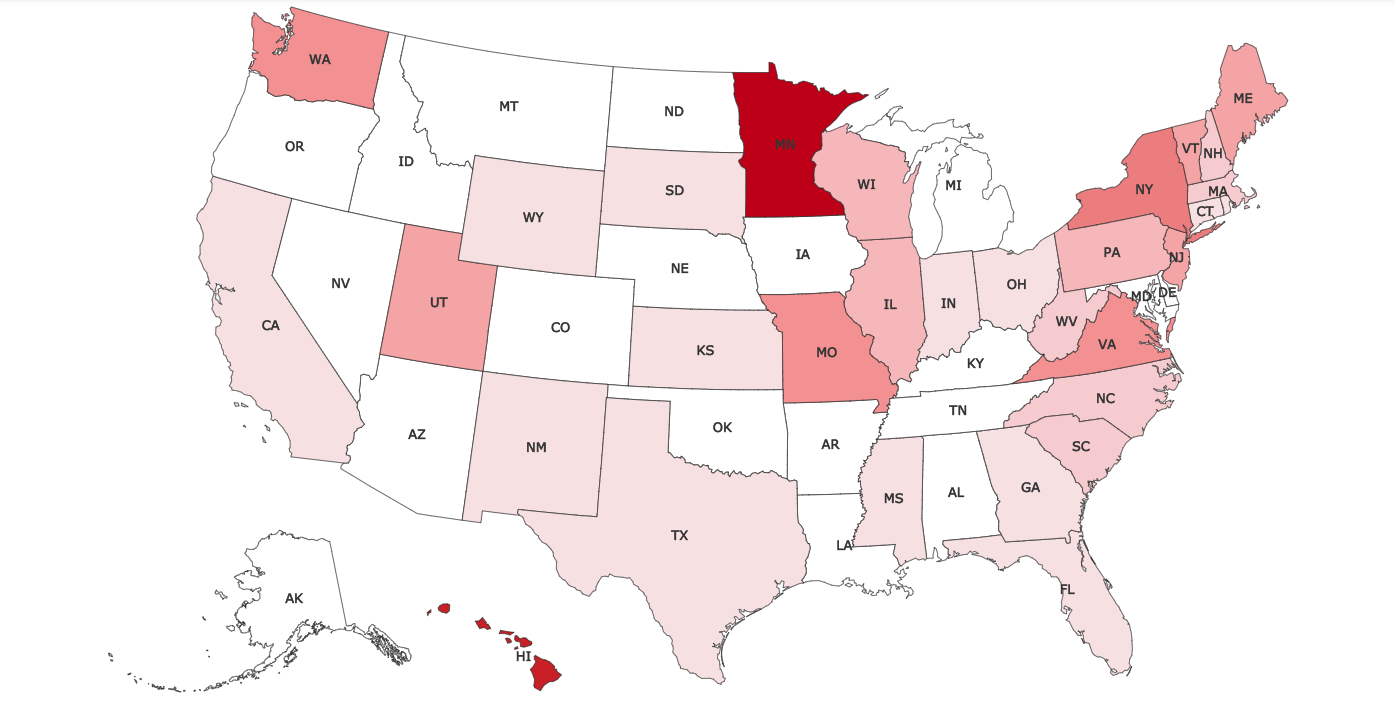

Electoral systems legislation

The map below shows which states have taken up electoral systems legislation this year. A darker shade of red indicates a greater number of relevant bills.

Electoral systems legislation in the United States, 2020

Current as of March 9, 2020

Primary systems legislation

The map below shows which states have taken up electoral systems legislation this year. A darker shade of red indicates a greater number of relevant bills.

Primary systems legislation in the United States, 2020

Current as of March 9, 2020