Ballotpedia’s 2019 ballot measure readability scores—How easy is it to understand what’s on your ballot?

I installed some new software the other day, and for once, I tried to understand the end-user license agreement that I had to approve before it would complete the installation. Some of it made sense, but there were other sections where I was pretty lost. That’s probably the case with any legal document.

I thought that some voters might feel the same way when faced with ballot measures when going to vote. It’s hard to be an informed citizen when you have trouble understanding what you’re reading. I was excited when our Ballot Measures editor told me it was time to publish our readability index.

For the third year in a row, we’ve taken ballot measure language and run it through industry-standard assessment tools to assign a readability rating. We ran the 2019 ballot titles and summaries for all 36 statewide ballot measures through formulas designed to measure the readability of text.

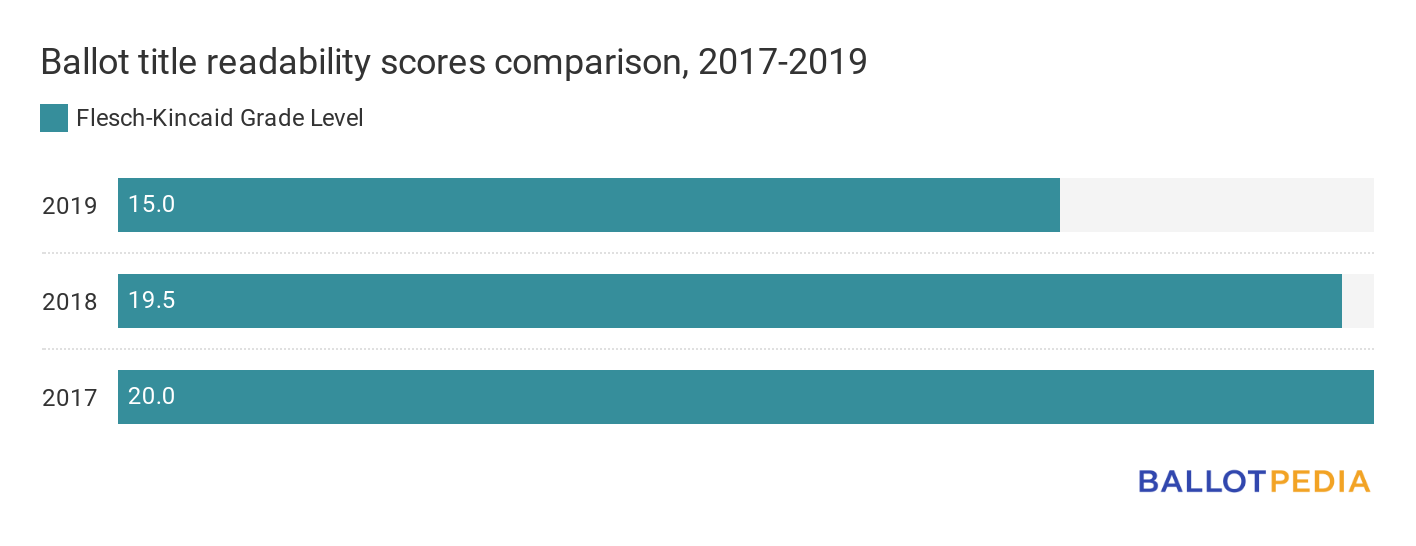

Overall, the average estimated number of years of U.S. education required to understand the text of ballot measure titles decreased compared to the last two years. We found that in 2019, 15 years of formal U.S. education is needed to understand ballot measure titles. That number was between 19 and 20 in 2018 and 20 in 2017.

Our ballot measures team used two formulas, the Flesch Reading Ease (FRE) and Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level (FKGL), to compute scores for the titles and summaries of ballot measures. The FKGL formula produces a score equivalent to the estimated number of years of U.S. education required to understand a text. The FRE formula produces a score between a negative number and 100, with the highest score (100) representing a 5th-grade equivalent reading level and scores at or below zero representing college graduate-equivalent reading level. Therefore, the higher the score, the easier the text is to read. Measurements used in calculating readability scores include the number of syllables, words, and sentences in a text. Other factors, such as the complexity of an idea in a text, are not reflected in readability scores.

Here are some highlights from Ballotpedia’s 2019 ballot language readability report:

-

The average Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level for the ballot titles of all 2019 ballot measures is 15 years of formal U.S. education. Scores ranged from 6 to 27 years.

-

The average Flesch Reading Ease score for the 2019 ballot measure titles is 26. The scores ranged from -22 to 69.

-

The average Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level for the ballot summaries or explanations of all the 2019 statewide ballot measures that were given a summary or explanation is 15 years of formal U.S. education. The average Flesch Reading Ease score for ballot measure summaries is 25.

-

The states with the lowest average Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level scores for ballot titles or questions are Washington, Pennsylvania, and Maine with 9, 10, and 17, respectively. This means that they require less formal education to understand the meaning of the titles.

-

The states with the highest average Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level scores for ballot titles or questions are Colorado, Kansas, and Texas with 27, 23, and 20. The titles from these states require greater levels of formal education to understand the meaning of the titles.

-

Average ballot title grades were lowest for language written by the Washington Attorney General (9) and initiative petitioners (10). Average ballot title grades were highest for language written by state legislatures (20).

How does this compare to prior years?

-

In 2017, there were 27 statewide measures in nine states. The average Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level for ballot measure titles was 20. Scores ranged from seven to 42.

-

In 2018, there were 167 statewide measures in 38 states. The average Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level for ballot measure titles was between 19 and 20. Scores ranged from eight to 42.

Ballotpedia also measures the word length of ballot titles across states. The states with the longest ballot titles or questions on average are Kansas, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Colorado; all of these except New Jersey did not feature additional ballot summaries or explanations. The states with the shortest ballot titles or questions on average are Texas, Maine, Louisiana, and Washington.

|