In recent weeks, policymakers across the country have postponed elections and otherwise modified their election procedures in response to the COVID-19 outbreak. In order to chart these developments with greater precision, we will, beginning this week, publish The Ballot Bulletin on a biweekly basis.

Elections in the midst of a pandemic: four experts speak to the challenges that lie ahead

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, dozens of states have either postponed upcoming elections or made modifications to voting and candidate filing procedures. This has prompted policymakers, pundits, voters, and others to discuss and debate the changes and challenges that might lie ahead We asked four election policy experts, each occupying a different point on the spectrum of debate, the following questions:

- What types of further modifications do you anticipate over the course of the next few months?

- What is the greatest challenge we face as we move out of the primary season and into the general election season?

Here are their responses.

Logan Churchwell: The biggest challenge is fear. States should not be reaching for increased mail balloting out of panic. There are several reasons for this. First and foremost, states do not maintain their voter rolls for accuracy to the level required to be throwing millions of ballots in the mail with any sort of automation. Too many states rely on polling place check-ins to be a last line of defense against an outdated record. Mail ballots go to the last address on file regardless if the person is dead, moved, registered in duplicate, or in prison. Second, local officials do not have the manpower for universal mail balloting nationwide. Hundreds of thousands or more human hands will be required to open envelopes, verify signatures, and handle the ballots for tabulation. Elections offices risk cutting into still scarce medical PPE supplies if this happens. In the best of times, this work is done largely by volunteers. Third, it makes no sense to close polling places down if Americans can still go grocery shopping whenever they want. Voting booths can be cleaned just as easy as the check-out aisle. Election officials should reach for the Lysol before massive changes to voting on shoestring budgets and little time. Finally, Americans tend to trust their elections because most saw with their own eyes that nothing went wrong in the voting place. That basic level of trust is ripped away with all voting in the mail.

- Logan Churchwell is Communications and Research Director of the Public Interest Legal Foundation, a law firm that “exists to assist states and others to aid in the cause of election integrity and fight against lawlessness in American elections.”

Edward Foley: What happened in Wisconsin should be a wake-up call that we can’t let anything like that happen again for the November election. What went wrong? While there’s plenty of blame to spread around among all three branches of Wisconsin’s government (legislature, governor, supreme court), the big-picture problem was failure to separate the health-specific question of whether in-person voting on Election Day was appropriate given the pandemic (short answer, no) from the election-question remedy of what adjustments to the voting process should be made, and by whom, as a consequence of the health necessity. The Wisconsin legislature and governor were locked in a partisan tug-of-war over who has the power to change the date of the election, when that wasn’t the relevant question. Instead, what mattered is who had the power to prohibit public gatherings at polling places, like sporting events and other public venues. The answer to that, as the dissenting opinion in the Wisconsin Supreme Court pointed out (by quoting the relevant state statute), was the state’s Department of Health Services. But by the time this observation was made (at the end of the night before Election Day), it was too late. As a result, Wisconsin was unable to achieve what Ohio successfully did, closure of the polls on Election Day to protect public health, with subsequent remediation of the electoral process in order to assure that all eligible voters had an adequate opportunity to cast a ballot in the election. Ohio’s remediation was accomplished, first, by the Secretary of State and then the state’s legislature modifying the remedial plan—an outcome that the federal court deemed constitutionally sufficient to protect voting rights.

Looking ahead to November, it’s essential to put in place plans for absentee voting that recognize both the need for substantially increased reliance on absentee ballots and the risks of problems, including litigation, that flows from greater use of absentee voting. Without spelling out all the details here, the basic principles must be (1) genuine opportunity for all eligible voters to cast a ballot without a health-related fear caused by COVID-19; and (2) reasonable measures to secure the integrity of the voting process for the benefit of the entire electorate. It is possible to satisfy both principles as long as there is the good will to do so, for the sake of electoral accountability (“governments … deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed”), rather than attempting to structure the voting process to secure a partisanship or incumbency advantage. If appropriate measures are adopted in advance, it will be significantly easier to avoid the kind of 5-4 U.S. Supreme Court decision that is so distressing to public confidence that the judicial enforcement of election rules is nonpartisan. The key is to prevent a situation where the outcome of the presidential election is perceived to rest on a vote tally that does not accurately reflect the will of the participating electorate because either (a) there has been an unremedied integrity breach, or (b) unremedied disenfranchisement of valid voters.

- Edward Foley is the Ebersold Chair in Constitutional Law at The Ohio State University. He also directs the university’s election law program. His most recent book, Presidential Elections and Majority Rule (Oxford University Press), was published earlier this year.

Walter Olson: The November 1918 national vote held during the Spanish flu epidemic was a triumph of legitimate democratic succession, but at some cost: turnout sagged and scholars say in-person rallies, permitted in the final days, spread the infection. We can do better. Whatever your previous thinking on absentee and vote-by-mail procedures, minimizing the need for in-person voting is now the need of the hour. Every vote cast by mail is one that doesn’t add to waiting lines (already a headache even before social distancing) and the need for interaction at sign-in tables.

Use of the mails aside, we should encourage as much of the process as we can to move online or even where appropriate outdoors (sunlight and fresh air probably disrupt virus transmission). Our greatest challenge is lack of time from being caught unprepared.

- Walter Olson is a senior fellow at the Cato Institute, a public policy research organization “dedicated to the principles of individual liberty, limited government, free markets and peace.” In 2015, Olson served as the Co-Chair of Gov. Larry Hogan’s Maryland Redistricting Reform Commission.

Drew Penrose: There are really two kinds of changes we have seen so far: changes to how voters can cast a ballot while still complying with all the measures in place to prevent spread of the disease, and changes to how candidates and campaigns comply with new COVID-19 restrictions. The former has gotten a lot of much-deserved attention, with more places making it possible for people to request absentee ballots, new deadlines for returning mailed-in ballots, and adjusting election dates entirely. We will certainly see more of that. The latter deserves additional attention as well: candidates and ballot measure campaigns were actively underway before COVID-19 hit us and made it impossible to gather petition signatures in-person. Although some states have adjusted petition requirements and deadlines, much more should be done, and several campaigns are bringing their cases into court. This issue is just as much about fairness to voters as it is fairness to these campaigns – ballot access is what determines what choices voters will have on their ballots, and having real choices when voting is absolutely critical to a functional democracy.

This crisis has demonstrated how frail much of our electoral infrastructure is. We need to make sure that the November election has safeguards in place to ensure that a representative democracy can survive and thrive beyond this pandemic. That includes more than just voting: in between the primaries and general election, we will have the national conventions of the political parties and candidates and ballot measure committees attempting to reach voters during the campaign itself. It will also be necessary for our legislatures and courts to be able to meet and do business to pass new rules and adjudicate important disputes prior to Election Day.

- Drew Penrose is Law and Policy Director for FairVote, a nonprofit group that describes itself as “a nonpartisan champion of electoral reforms that give voters greater choice, a stronger voice, and a representative democracy that works for all Americans.

Wisconsin’s April 7 election proceeds as 17 other states postpone March, April, and May state-level elections

Wisconsin’s spring elections proceeded as scheduled on April 7. The elections on the ballot included the state’s Democratic presidential primary, a state supreme court and three state appeals court elections, a statewide ballot measure, and several municipal and school board contests.

On April 6, the Wisconsin Supreme Court voted 4-2 to block an executive order issued earlier in the day by Governor Tony Evers (D) that would have postponed in-person voting in the spring elections to June 9. As a result, in-person voting proceeded as scheduled. Also on April 6, the U.S. Supreme Court voted 5-4 to stay a lower court order that had extended the absentee voting deadline. As a result, the absentee ballot postmark and in-person return deadlines were both reinstated to April 7.

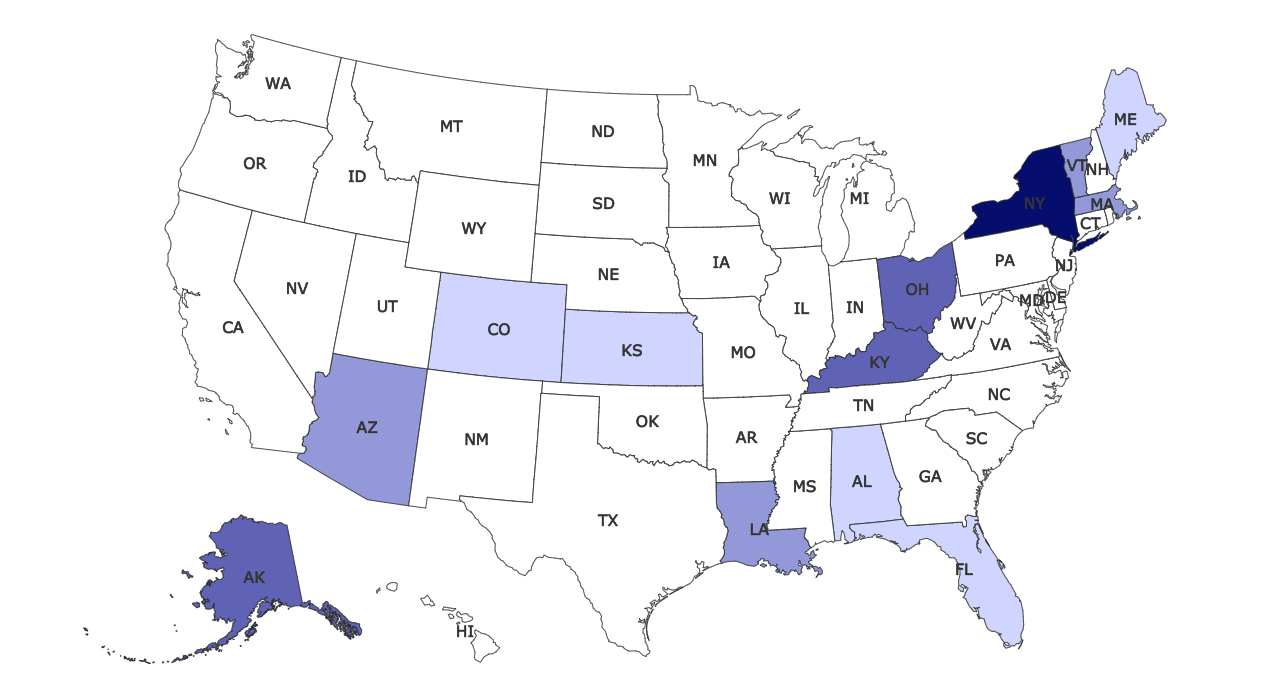

Meanwhile, 17 states and one territory that were scheduled to conduct state-level elections in March, April, or May, have postponed them. These states are colored in dark blue on the map below. In another six states, state-level officials have modified, or have authorized the modification of, municipal election dates. These states are colored in light blue on the map below. Further details are provided below the map.

- Alabama: Primary runoff, originally scheduled for March 31, postponed to July 1.

- Connecticut: Presidential primary, originally scheduled for April 28, postponed to June 2.

- Delaware: Presidential primary, originally scheduled for April 28, postponed to June 2.

- Georgia: Presidential primary, originally scheduled for March 24, postponed to May 19.

- Indiana: Primary, originally scheduled for May 5, postponed to June 2.

- Kentucky: Primary, originally scheduled for May 19, postponed to June 23.

- Louisiana: Presidential primary, originally scheduled for April 4, postponed to June 20.

- Maryland: Primary, originally scheduled for April 28, postponed to June 2.

- Massachusetts: Two special state Senate elections, originally scheduled for March 31, postponed to May 19. Two special state House elections, originally scheduled for March 31, postponed to June 2.

- Mississippi: Republican primary runoff for the state’s 2nd Congressional District, originally scheduled for March 31, postponed to June 23.

- New York: Presidential primary, originally scheduled for April 28, postponed to June 23. Special elections in the following districts also postponed to June 23: 27th Congressional District, State Senate District 50, State Assembly District 12, State Assembly District 31, State Assembly District 136.

- North Carolina: Republican primary runoff for North Carolina’s 11th Congressional District, originally scheduled for May 12, postponed to June 23.

- Ohio: Absentee voting in the state’s primary, originally scheduled for March 17, extended to April 27. Final date for in-person voting, restricted to individuals with disabilities and those without home mailing addresses, set for April 28.

- Pennsylvania: Primary, originally scheduled for April 28, postponed to June 2.

- Puerto Rico: Democratic presidential primary, originally scheduled for March 29, postponed to an unspecified future date.

- Rhode Island: Presidential primary, originally scheduled for April 28, postponed to June 2.

- Texas: Special election for Texas State Senate District 14, originally scheduled for May 2, postponed to July 14. Primary runoffs, originally scheduled for May 26, postponed to July 14.

- West Virginia: Primary, originally scheduled for May 12, postponed to June 9.

Legislation tracking

To date, we have tracked 32 bills that make some mention of both election policy and COVID-19. States with higher numbers of relevant bills are colored in darker blue on the map below. States with lower numbers of relevant bills are colored in lighter blue. In states colored white, we have tracked no relevant bills.

Legislation related to elections and COVID-19, 2020

Current as of April 7, 2020

Looking ahead

Looking ahead

In our next issue, due out April 22, we will examine the legal mechanisms states can use to modify or postpone elections. We will also take a closer look at those states that have temporarily expanded absentee voting.