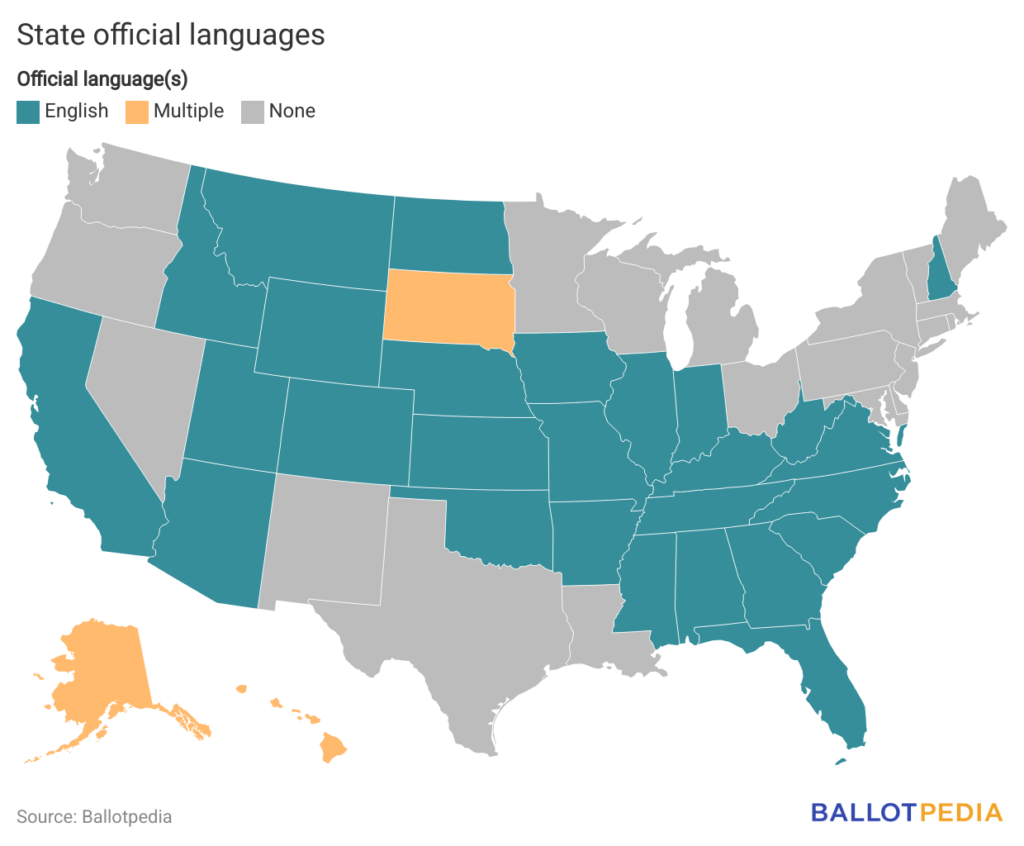

President Donald Trump (R) issued an executive order “[designating] English as the official language of the United States” on March 1, 2025. While the federal government had never before provided for an official national language, 30 states have designated English as their official language. Three—Alaska, Hawaii, and South Dakota—also recognize some indigenous languages as co-official languages. Most (27) of these states adopted their official language between the 1980s and 2000s, with a median year of 1988.

In 1991, Michele Arington wrote that “[a]lthough a proposed [federal] constitutional amendment, the ‘English Language Amendment,’ has stalled repeatedly in the Congress,” supporters had “considerable success at the state and local levels.” Arington added, “The preferred method of enacting such legislation, especially in recent years, has been the initiative and referendum.” The trend emerged in the 1980s with California Proposition 63 and continued into the 2000s, with the most recent vote taking place in 2010 in Oklahoma.

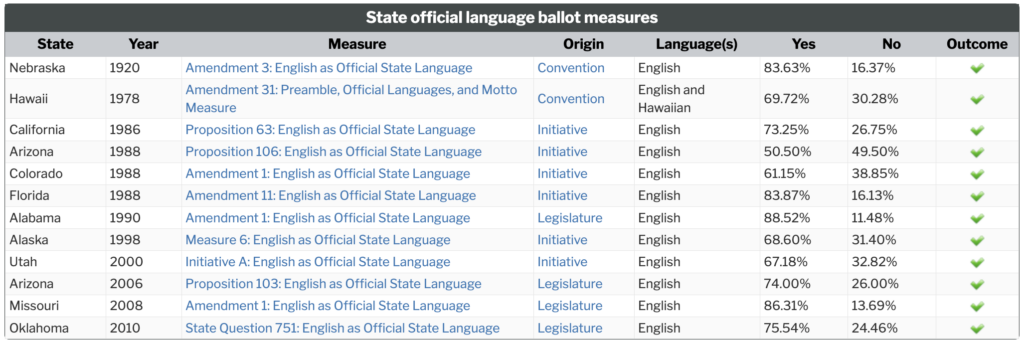

Of the 30 states that designated English as their official language, 11 (37%) did so through voter-approved ballot measures. Measures were approved in Alabama, Alaska, California, Colorado, Florida, Hawaii, Missouri, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Utah, and twice in Arizona. The average vote on these measures was 73.1%, with support ranging from 50.5% to 88.5%.

Nebraska was the first state to vote on an official language ballot measure. In 1920, voters approved Amendment 3, designating English as the official language of Nebraska and requiring that public school subjects be taught in English.

Oklahoma was the most recent state to vote on a measure, with voters approving State Question 751 in 2010. The ballot measure declared English the “common and unifying language of the State of Oklahoma” and required that all official state actions be conducted in English, with exceptions.

The ballot measure that received the highest approval margin was Alabama Amendment 1, receiving 88.5% of the vote, in 1990. Amendment 1 established English as the state’s official language; prohibited laws that diminish or ignore “the role of English as the common language of the state of Alabama;” and granted residents standing to sue the state for enforcement.

The ballot measure that received the narrowest approval margin was Arizona Proposition 106, receiving 50.5% of the vote, in 1988. Proposition 106 designated English as the official language of Arizona and required governmental actions, functions, and documents to be conducted in English, with exceptions. In Ruiz v. Hull, the Arizona Supreme Court ruled that Proposition 106 violated the First Amendment and Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution on April 28, 1998, rendering the citizen-initiated constitutional amendment inoperative.

In 2006, the Arizona State Legislature referred a constitutional amendment, Proposition 103, to the ballot. Proposition 103 also designated English as the official language of Arizona. However, while Proposition 106 required governmental actions, functions, and documents to be conducted in English, Proposition 103 required government representatives to protect and promote English in official functions while allowing unofficial multilingual communication. Proposition 106 was approved with 74.0% of the vote.

Of the 30 states with such laws, 10 enacted them through a ballot measure. Missouri first passed a legislative statute and later approved a constitutional amendment ballot measure. Therefore, 11 of the 30 states adopted official language laws through ballot measures.

While the ballot measures each sought to designate English as an official state language, the measures differed in terms of application and enforcement. Selected from official voter information pamphlets, the following arguments for and against the ballot measures focus on the provision designating English as the official language, as this was the common provision uniting the measures.

Supporters of these ballot measures argued that establishing English as an official language would promote cultural assimilation, unity, and a shared American identity.

- California Proposition 63 (1986): Former U.S. Sen. Samuel Ichiye Hayakawa (R-California) said there is a “serious erosion of English as our common bond” due to language conflicts.

- Arizona Proposition 103 (2006): State Rep. Russell Pearce (R) stated that “a common language promotes unity and understanding and is as vital to the health of a nation as having a common currency.”

- Alaska Measure 6 (1998): Former Attorney General Edgar Paul Boyko said English, like national symbols, “reminds Americans and Alaskans of every race, religion, and background of what we all have in common.”

Opponents of these ballot measures argued that making English the official language would be unnecessary, foster division, and could lead to legal challenges.

- California Proposition 63 (1986): Attorney General John Van De Kamp (D) said the policy “will produce a nightmare of expensive litigation and needless resentment.”

- Arizona Proposition 103 (2006): State Sen. Jorge Luis Garcia (D) and State Rep. Ben Miranda (D) stated, “Since there is not a rational basis to make English Arizona’s ‘official’ language, we are left to conclude that Proposition 103 is directed at Spanish speakers. Proposition 103 is a measure that is steeped in hate.”

- Alaska Measure 6 (1998): Jennifer Rudinger, executive director of the ACLU of Alaska, said the law “merely fosters divisiveness by saying to our indigenous and non-English speaking residents that they are not accepted in Alaska.”

Additional reading: