Welcome to Hall Pass, a newsletter written to keep you plugged into the conversations driving school board governance, the politics surrounding it, and education policy.

In today’s edition, you’ll find:

- On the issues: The debate over no-zero grading policies

- School board filing deadlines, election results, and recall certifications

- The right of first refusal: charter school access to district property

- Extracurricular: education news from around the web

- Candidate Connection survey

- School board candidates per seat up for election

Reply to this email to share reactions or story ideas!

On the issues: The debate over no-zero grading policies

In this section, we curate reporting, analysis, and commentary on the issues school board members deliberate when they set out to offer the best education possible in their district. Missed an issue? Click here to see the previous education debates we’ve covered.

Grades are a critical measure of student success, influencing class placement, access to Advanced Placement courses, college admissions, and high school graduation eligibility. Traditionally, teachers have assigned grades based on a 0-100% scale. Under this system, students receive an F for any work scored between 0-60%. In many schools, students receive zeroes for failing to turn in assignments on time.

Depending on the weight of the missed assignment, receiving a zero under the 0-100% scale can drastically lower a student’s overall grade, requiring high marks on future assignments to recover a desired average — or even a passing grade. In recent years, some districts have implemented no-zero grading policies and placed a floor—such as 50%—below which students’ grades cannot fall.

Education researcher Daniel Buck argues that no-zero grading policies lower expectations for students, discouraging many from trying their hardest on assignments. Buck says the traditional grading scale, while imperfect, is easy for teachers to implement, and does an adequate job capturing intangible student characteristics—such as discipline—that predict success later in life. He proposes several alternatives to the traditional grading system that he says are superior to no-zero policies.

Education consultant and author Douglas B. Reeves argues that, under the 0-100% scale, zeroes are an excessive response to unsubmitted work rooted in vengeance and an erroneous belief that punishment will motivate students to do better. Reeves says teachers are more likely to motivate students by removing privileges, such as free time, when assignments are not completed. Reeves recommends that, if schools want to keep the zero, they adopt what he considers a fairer four-point scale where F equals zero and each grade is proportionally separated by one point.

A “no zeroes” grading policy is the worst of all worlds | Daniel Buck, Thomas B. Fordham Institute

“In our modern iteration, that 60 percent represents more than a proportionate designation of points. The grades D represents the barest minimum of what a school or teacher considers acceptable by way of student learning. Below that is completely unacceptable, deserving of no credit, no points, no reward. Understood so, the current system tilts toward mastery, even excellence, thereby incentivizing students to more than mere completion.

What’s more, eliminating the zero invites all sorts of problems. If a student anticipates failing a test, project, or essay, how many will simply avoid any attempt, knowing that only a 50 percent awaits? Whereas a 0 percent weighs heavily on someone’s final grade, and so incentivizes students to make corrections or seek out additional help, how many students will instead just accept a mediocre final grade? What are the knock-on effects of ever-worsening grade inflation? What implicit message does it communicate to students when no effort receives half points?”

The case against zero | Douglas B. Reeves, The Phi Delta Kappan

“If I were using a four-point grading system, I could give a zero. If I am using a 100-point system, however, then the lowest possible grade is the numerical value of a D, minus the same interval that separates every other grade. In the example in which the interval between grades is 10 points and the value of D is 60, then the mathematically accurate value of an F is 50 points. This is not — contrary to popular mythology — ‘giving’ students 50 points; rather, it is awarding a punishment that fits the crime. The students failed to turn in an assignment, so they receive a failing grade. They are not sent to a Siberian labor camp.

There is, of course, an important difference. Sentences at Siberian labor camps ultimately come to an end, while grades of zero on a 100-point scale last forever. Just two or three zeros are sufficient to cause failure for an entire semester, and just a few course failures can lead a student to drop out of high school, incurring a lifetime of personal and social consequences.”

School board update: filing deadlines, election results, and recall certifications

In 2025, Ballotpedia will cover elections for more than 30,000 school board seats. We’re expanding our coverage each year with our eye on covering the country’s more than 80,000 school board seats.

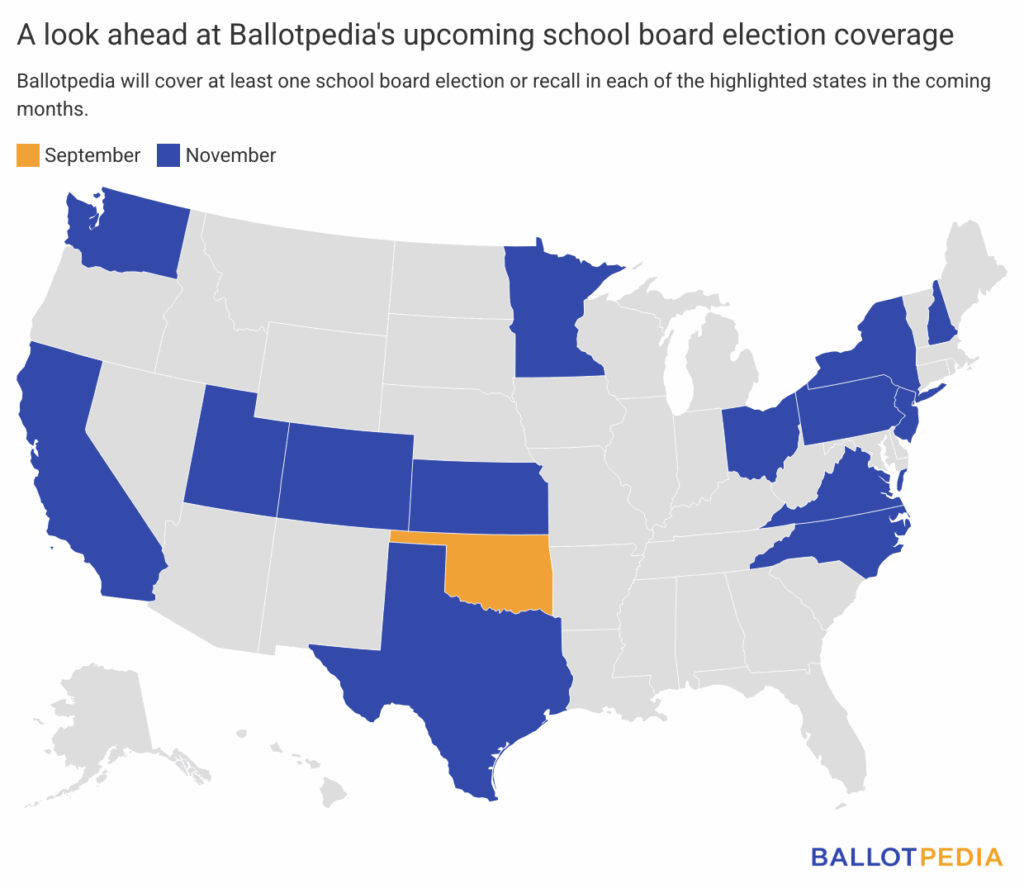

The next major wave of school board elections will occur on Election Day, Nov. 4, in at least 14 states. Stay tuned for more on Ballotpedia’s coverage of November school board elections.

The right of first refusal: charter school access to district property

Unlike traditional public schools, charter schools cannot issue bonds to pay for building construction or expansion, and many states don’t provide funding for charter school facilities. The onus is often on charter schools to secure a space to operate.

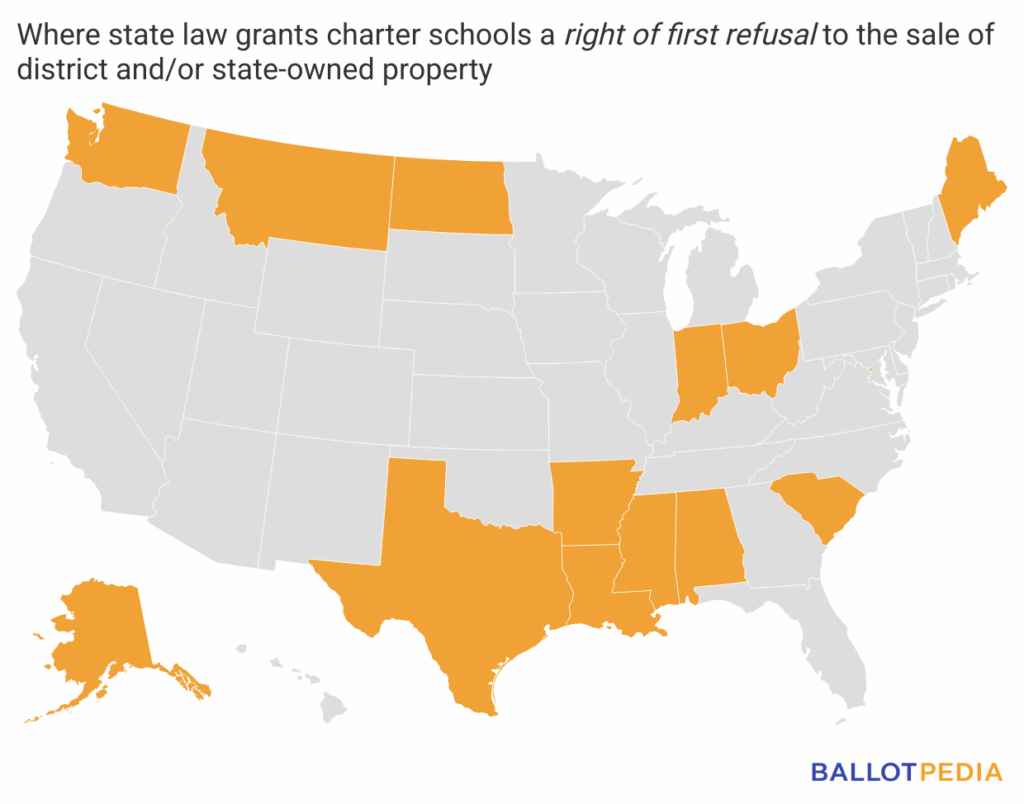

One way some states assist charter schools in acquiring facilities is the legal principle known as the right of first refusal, which gives charter schools first dibs to any unused—sometimes called “surplus”—school district or state-owned property up for sale. At least 14 states include this provision in their charter school laws, but not without controversy. Supporters say the policy is meant to help charter schools find facilities, while critics say it weakens district control.

Charter schools and access to facilities

Charter schools are public schools that operate outside the traditional school system. Private organizations, typically but not always nonprofits, contract with the state, school district, or some other authorizing body to meet certain academic requirements. In exchange, charter schools are granted greater autonomy than traditional districts over curriculum, personnel, scheduling, and more. Minnesota passed the first law authorizing charter schools in 1991. Since then, all but three states—Nebraska, South Dakota, and Vermont—have followed in Minnesota’s footsteps.

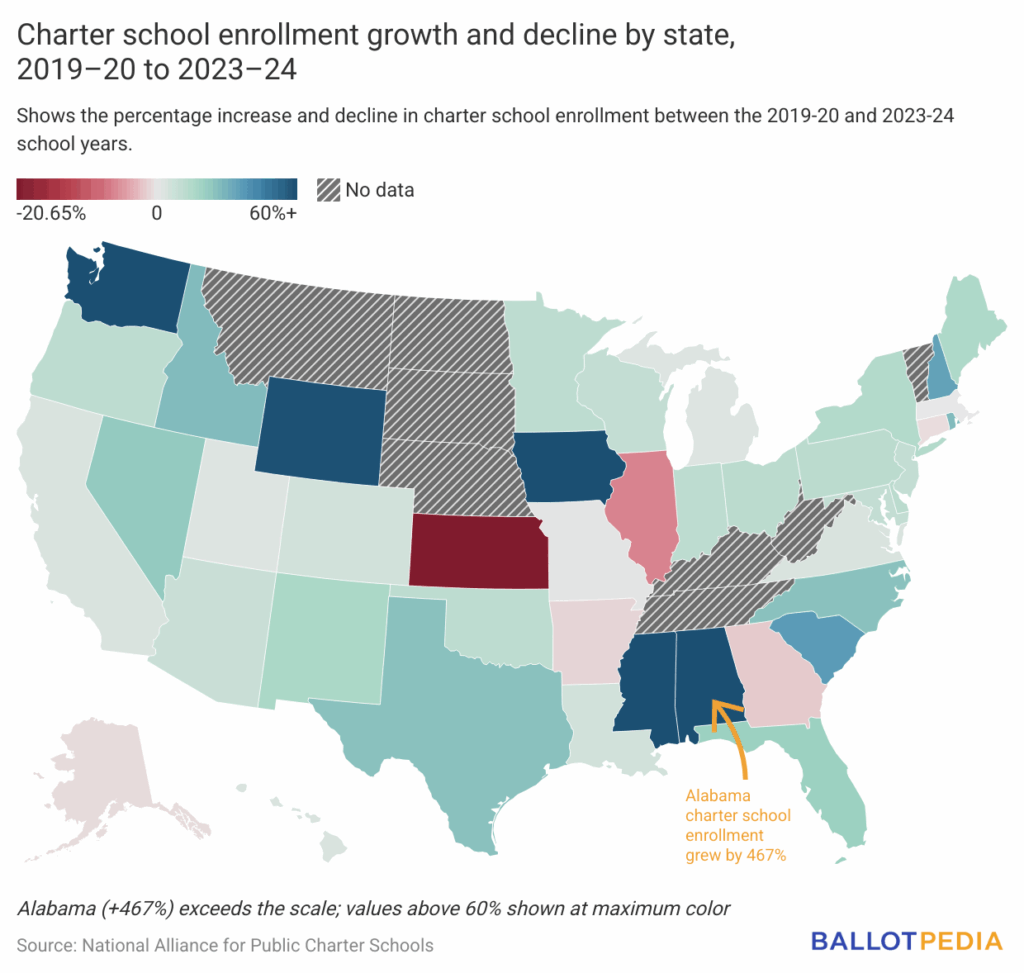

During the 2023-24 school year, charter schools enrolled 3.7 million students, up from 3.4 million in 2019.

Click here to read Hall Pass’ primer on charter schools.

Charter school advocates and education analysts have long argued that access to facilities is a chokepoint for the sector’s growth. A 1999 U.S. Department of Education report found that “newly created charter schools cited lack of start-up funds and inadequate facilities as the most common barriers to implementing their charters.”

Because charter schools aren’t guaranteed facilities, they must often pay for buildings and maintenance out of their general operating funds, take out commercial loans, or rely on funding from government grants or private sources. Nonprofit organizations like the Walton Family Foundation, for example, have established national charter school facility funds which charter schools can apply for. The U.S. Department of Education has also created several grant programs that assist charter schools with funding facilities.

States have implemented various policies meant to help charter schools gain access to facilities, including the right of first refusal and requiring that districts share underused space on their campuses.

Where states give charter schools a right of first refusal

At least 14 states give charter schools the right of first refusal to state-owned and district property before it goes on the market. The specifics vary by state, but the laws generally say districts must offer property to charter schools first at a fair market price. Only after charter school organizations have turned down the property can districts offer it to a wider category of potential buyers.

Some states, like Ohio, require districts to offer unused property to charter schools. Ohio Revised Code Section 3313.411 defines “unused school facilities” as those that have not been used for academic or administrative purposes for one year or have been used for academic purposes but only at 60% capacity. However, according to the Center on Reinventing Public Education, “‘Surplus’ lacks specific meaning in most laws and districts remain the decisionmakers, often reluctant to let go of facilities they feel they might later need.”

The fight over vacant school buildings

Traditional public schools and charter schools have had a complex relationship marked by both collaboration and tension since 1991. Some districts have viewed charters as partners in education, even serving as authorizing entities, while others have seen them as competitors angling for the same pool of students.

In states without right of first refusal laws, districts have sometimes used deed restrictions to prevent buyers from turning public school district facilities into homes for charter or private schools. Consider the examples of Illinois and Michigan.

Earlier this year, Chicago Public Schools (CPS) decided to sell 20 properties that had been vacant for more than a decade. The district prohibited buyers from turning the properties into charter schools or liquor stores. In Michigan, lawmakers passed the 2017 Educational Instruction Access Act after the Detroit Public Schools Community District restricted the new owner of an old elementary school from selling it to a charter school organization.

Critics of right of first refusal laws say they are undemocratic limitations on local district autonomy and that they encourage schools to think about short-term financial gain over the needs of the community. But proponents say the laws give charter schools an opportunity to use school facilities for their intended use instead of sitting vacant or being sold to developers.

This year in Arizona, where charter organizations cannot be excluded from purchasing unused district property, lawmakers considered a bill to give charter organizations the right of first refusal. State Rep. Matt Gress (R) sponsored HB 2640, and it passed the House and Senate along partisan lines, with all Democrats voting against it. Save our Schools Arizona, a group that advocates for greater public school funding and an end to the state’s private school choice programs, criticized the bill. Save Our Schools Arizona Director Beth Lewis said, “With schools facing closures a lot of times that’s temporary or they can repurpose the campus to be like an early child Learning Center, something great for the community instead of selling it off to a private school.”

On April 18, Gov. Katie Hobbs (D) vetoed HB 2640. Arizona House Republicans said: “This was a commonsense measure to expand educational opportunity, protect school choice, and ensure taxpayer resources benefit Arizona children—not politics.”

Extracurricular: education news from around the web

This section contains links to recent education-related articles from around the internet. If you know of a story we should be reading, reply to this email to share it with us!

- Reading Skills of 12th Graders Hit a New Low | The New York Times

- Another School Year, Another School Shooting | The 74

- Pennsylvania faces severe teacher shortage, calls for legislative action | WGAL

- Artificial intelligence is here. Will it replace teachers? | ABC News

- The United Nations Says Teacher Shortages Are a Global Problem | Education Week

- California discipline data show widespread disparities despite reforms | K-12 Dive

- Why have books disappeared from many ELA curricula? | The Curriculum Insight Project

- Head Start Funding Is on Track for Approval. It Still May Not Be Enough. | EdSurge

- Education Doesn't Work 3.0: a comprehensive argument that education cannot close academic gaps | Freddie DeBoer, Substack

Take our Candidate Connection survey to reach voters in your district

Today, we’re looking at surveys from two of the six candidates running in the Nov. 4 general election for three at-large seats on the South-Western City Schools Board of Education, in Ohio.

Incumbent Camille Peterson was appointed to the board in 2023. Her career experience includes working as a social worker. Kelly Dillon’s career experience includes working as a professor and in research management/support.

South-Western is the fourth-largest district in Ohio, with approximately 22,000 students. It is located southwest of Columbus.

Here’s how Peterson answered the question, “What areas of public policy are you personally passionate about?”

“Public Education Funding and Vouchers-I respect every parent’s right to choose the educational setting that best fits their child, whether public, private, charter, or homeschool. However, I do not support using public tax dollars to fund private or charter school tuition through voucher programs. Public education dollars are meant to serve our community’s students in neighborhood schools. Diverting these funds to private institutions reduces resources for critical programs, staff, and services in our public schools—schools that serve all students, regardless of income, ability, or background. As funding is redirected, districts are forced to depend more on local property taxes, increasing the burden on homeowners, this is unfair.”

Click here to read the rest of Peterson’s responses.

Here’s an excerpt from Dillon’s answer to the question, “What are the main points you want voters to remember about your goals for your time in office?”

“Learners of all types have equal opportunities to thrive. Our district covers over 119 square miles including over 21,000 students and hundreds of small neighborhoods - urban, rural, and suburban. It is time each school has opportunities for students to thrive, discover, and build key skills. There is no reason why a school in a Columbus city zip code doesn't have the same clubs, classes, or leadership as one in a Grove City neighborhood. Our diversity of cultures and environments in our district is our STRENGTH. Let's tap into that diversity, learn from each other, and help shape our children for a global economy.”

Click here to read the rest of Dillon’s responses.

In the 2024 election cycle, 6,539 candidates completed the survey, including over 500 school board candidates.

If you're a school board candidate or incumbent, click here to take the survey.

The survey contains over 30 questions, and you can choose the ones you feel will best represent your views to voters. If you complete the survey, a box with your answers will display on your Ballotpedia profile. Your responses will also appear in our sample ballot.