Welcome to the Friday, Sept. 26, 2025, Brew.

By: Lara Bonatesta

Here’s what’s in store for you as you start your day:

- Most states allow teenagers to pre-register to vote before turning 18, and some let them vote in primaries

- How endorsements can help provide voters with robust information, by Leslie Graves, Ballotpedia Founder and CEO

- Juneau, Alaska, voters to decide three local ballot measures on Oct. 7, including a seasonal sales tax proposal

Most states allow teenagers to pre-register to vote before turning 18, and some let them vote in primaries

While the minimum voting age in the United States is 18, every state with voter registration allows teenagers to pre-register to vote before they blow out the candles on their 18th birthday. North Dakota is the only state that does not have voter registration.

Pre-registration is a procedure in which people younger than 18 can fill out an application to register to vote. According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, pre-registrants are typically added to their state’s voter registration list, with a “pending” or “preregistration” status. This designation is removed when the pre-registrant turns 18 and is eligible to vote.

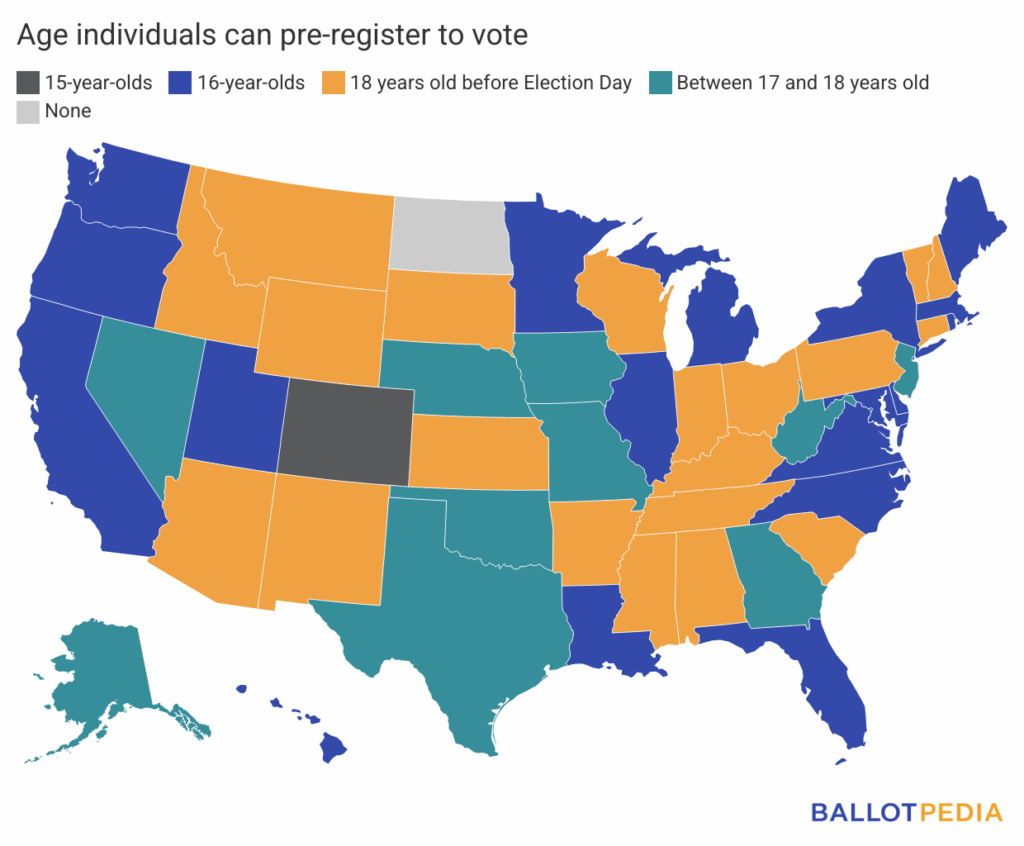

The age at which individuals can pre-register varies from state to state:

- Twenty states allow anyone who will be 18 years of age at the time of the next election to pre-register

- Ten states allow at least some 17-year-olds to pre-register

- Eighteen states and the District of Columbia allow 16-year-olds to pre-register

- Colorado allows 15-year-olds to pre-register

In 2024, states reported to the U.S. Election Assistance Commission (EAC) that more than 1.1 million individuals pre-registered to vote. California had the most pre-registrants, with 244,996. According to the U.S. Census, a total of 174 million people (or 73.6%) of the citizen voting-age population were registered to vote in the 2024 presidential election. Of those 154 million (or 65.3%) voted.

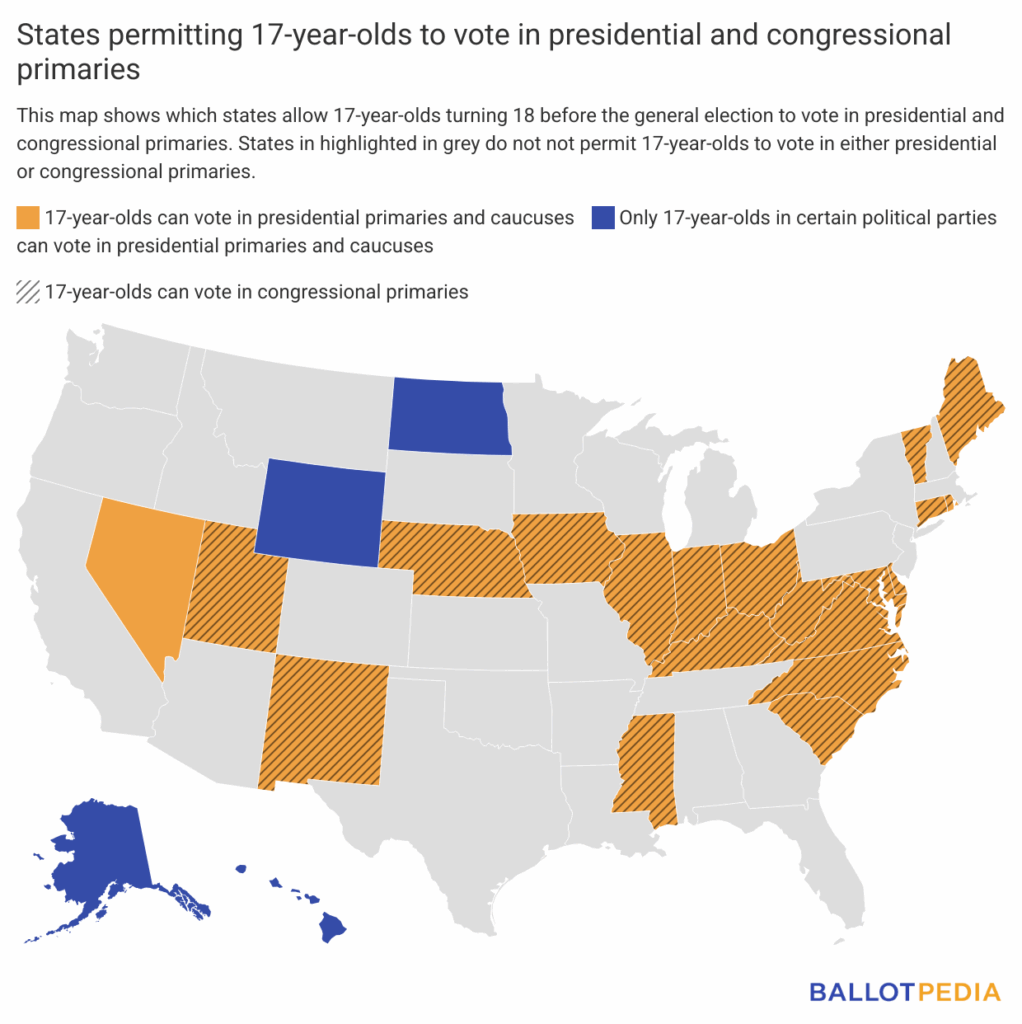

Generally, individuals who pre-register to vote are not allowed to cast a ballot until they turn 18, except in the states that allow 17-year-olds to vote in primary elections if they will be 18 before the general election.

- Nineteen states and the District of Columbia allow 17-year-olds who turn 18 by the general election to vote in that year's congressional primaries.

- Twenty states and the District of Columbia allow 17-year-olds to vote in the presidential primaries and/or caucuses of both major parties. In an additional four states, 17-year-olds can only participate in Democratic presidential primaries and/or caucuses.

Supporters of youth pre-registration say that the laws increase voter engagement among young people and reduce logistical hurdles for voter registration.

In 2023, Michigan Rep. Betsy Coffia (D), who introduced a bill expanding youth pre-registration to 16-year-olds, said young people "really are looking for ways to become more involved, and so this feels like just another step to smooth that path for them to be all set to go at 18." At the time, interim East Lansing City Clerk Marie Wicks said pre-registration would "be a huge time saver for us," as it could prevent long lines at polling places on college campuses.

Opponents of youth pre-registration laws say that the laws create administrative challenges.

Michigan Rep. Jay DeBoyer (R) said that because "youth may move between that registration and their first chance to vote, information may frequently be no longer accurate or valid." North Carolina Sen. Bob Rucho (R), who supported a bill repealing a youth pre-registration law, said it posed logistical problems for election officials and was "way too confusing and way too difficult to administrate."

Click here to learn more about youth pre-registration across the United States.

How endorsements can help provide voters with robust information

The very first column I wrote in this series addressed one of the most important components of what we consider “robust information” — Ballotpedia's Candidate Connection Survey. In today’s column, I want to take a deeper dive into another item on the robust information list: endorsements.

Most Daily Brew readers will have a solid grasp of what endorsements are and what they mean to individual candidates. But just in case, here’s a quick refresher: Endorsements are statements or actions that an individual or group provides in support of a candidate.

That’s the basic definition, but endorsements are much more than that. Endorsements reveal alliances, ideological leanings, and potential policy priorities in ways that campaign platforms and quotes from a candidate sometimes can’t.

Endorsements also play a practical role in campaigns. Many endorsers — especially for statewide and national candidates — can provide candidates with volunteer support, access to possible campaign donors, and give candidates a degree of credibility and notoriety.

But what about endorsements for local offices — the ones that usually don’t get the same level of media interest or satellite group involvement?

At this level, endorsements play a slightly different role because most local elections are nonpartisan. In these races, candidates run without party labels, and no such identification appears next to their names on the ballot. This means voters can’t rely on the party label that typically gives them a quick understanding of what a candidate stands for.

To give you a sense of how common these sorts of contests are:

- Since 2023, 58 percent of the 66,000 local elections we’ve covered have been nonpartisan.

- Roughly 90 percent of all elections for school boards are nonpartisan.

- Nineteen states hold nonpartisan elections for at least some judges.

That’s a big reason why we’ve put endorsements on our list of data points that make up robust information and why we try to collect endorsement information for as many candidates as possible.

Collecting this information for local candidates, though, is a big challenge. Part of the issue is that there are more than 500,000 local offices, and many of those elections will have multiple candidates. For elections in big cities, state capitals, and large school districts, endorsements are generally easier to identify.

But finding endorsements in smaller communities and those where local media coverage has either been greatly reduced or eliminated entirely can be a big challenge. The same goes for campaigns that have little or no online presence.

And then there are the campaigns for local offices, where no outside group is endorsing candidates — and many never have.

That means we have to look elsewhere for robust data — such as pledges candidates have signed or agreed to, or ratings of candidates from outside organizations. I’ll look at those in my next column.

Juneau, Alaska, voters to decide three local ballot measures on Oct. 7, including a seasonal sales tax proposal

Voters in Juneau, Alaska, will decide on three local ballot measures on Oct. 7, including two citizen initiatives and a referred measure to implement a new seasonal sales tax rate.

Currently, the sales tax rate in Juneau is 5% year-round—this includes a permanent 1% sales tax, a temporary 3% sales tax, and another temporary 1% sales tax. Proposition 3, which the City and Borough of Juneau Assembly put on the ballot, would repeal both the permanent 1% sales tax and the temporary 3% sales tax. They would be replaced with two seasonal rates—a 2% sales tax from Oct. 1 through March 31 and a 6.5% sales tax from April 1 through Sept. 30. This means that the total sales tax Juneau residents would pay would be 3% from October through March, and 7.5% from April through September.

A seasonal sales tax, or a fluctuating sales tax, is a tax rate that changes depending on the time of year. Municipalities sometimes use these taxes to charge higher rates during busy tourist months and a lower rate in the off-season for residents.

Juneau Assemblymember Neil Steininger spoke in support of Proposition 3, saying, "We have a lot of out-of-town visitors, and we have a lot of economic activity from non-residents in the summer. It allows us to shift some of that tax burden away from residents, making it even more affordable for individual residents in Juneau."

The City and Borough of Juneau Assembly put Proposition 3 on the ballot in response to Propositions 1 and 2, which Juneau voters will also decide on Oct. 7. Proposition 1 would decrease the property tax limit in Juneau, and Proposition 2 would create a sales and use tax exemption for food and non-commercial utilities.

Assemblymember Christine Woll, who supports Proposition 3, said that if voters approve Propositions 1 and 2, the city would face a revenue shortfall, and Proposition 3 would shift more of the tax burden to tourists to offset it. She said, "The seasonal sales tax basically will make up for that $9 to $12 million revenue loss by shifting the tax burden from residents to our summer visitors." Both Woll and Steininger spoke in support of Proposition 2 and 3 together, but said that only voting on Proposition 2 without voting on 3 would create a reduction in city revenue.

The Affordable Juneau Coalition, the organization that worked to place Propositions 1 and 2 on the ballot, is opposing Proposition 3. Angela Rodell, treasurer of the Affordable Juneau Coalition, said, “It needs to go back to the drawing board. They need to do a better job about defining how it’s going to help the residents of this community.”

The Greater Juneau Chamber of Commerce also spoke out against Proposition 3, saying it would negatively affect industries such as construction, which operate during the summer, when the sales tax would be higher, and could be complicated for businesses.

Six other Alaska municipalities have a seasonal sales tax. For most municipalities, the “on-season,” when tourists are more likely to visit, is from April to September, and the “off-season” is from October to March.

Click here to learn more about the Oct. 7 ballot measures in Juneau, Alaska.