Welcome to the Friday, Nov. 7, 2025, Brew.

By: Lara Bonatesta

Here’s what’s in store for you as you start your day:

- Twenty-three states have amended their absentee/mail-in voting laws so far this year

- One election ends, another begins: The 2026 midterm campaigns are already underway, by Leslie Graves, Ballotpedia Founder and CEO

- Federal government shutdown now longest in U.S. history

Twenty-three states have amended their absentee/mail-in voting laws so far this year

On Tuesday, Nov. 4, Maine voters defeated Question 1, which would have changed the state's absentee voting laws, limited ballot drop boxes, and required voter ID for individuals voting both in person and by absentee ballot. As of 12 p.m. EST on Nov. 5, the vote was 63.5%-36.5%, with 89% of votes in.

While Mainers rejected Question 1, lawmakers enacted three bills modifying the state’s absentee voting policies earlier this year, making Maine one of 23 states to amend its absentee/mail-in voting laws so far in 2025.

Maine lawmakers approved laws creating an alternative method of absentee/mail-in voting for mental health residential facilities or facilities serving individuals with intellectual disabilities, requiring a study on the possibility of providing digital access to local absentee ballots for uniformed service voters or overseas voters, and changing the timeframe for in-person absentee/mail-in voting in a clerk’s office.

So far this year, state legislators have introduced 413 bills related to absentee/mail-in voting. Forty-three bills in 23 states have become law. Three states — Kansas, North Dakota, and Utah — moved up the deadline by which election officials must receive absentee/mail-in ballots in order for them to be counted. Two states, New Hampshire and Utah, passed new requirements for voters to present identification or provide an identification number when voting or requesting an absentee/mail-in ballot.

Eighteen states adopted 31 laws related to absentee/mail-in voting in 2024. Thirty-four states adopted 67 such laws in 2023. Twenty states adopted 38 such laws in 2022.

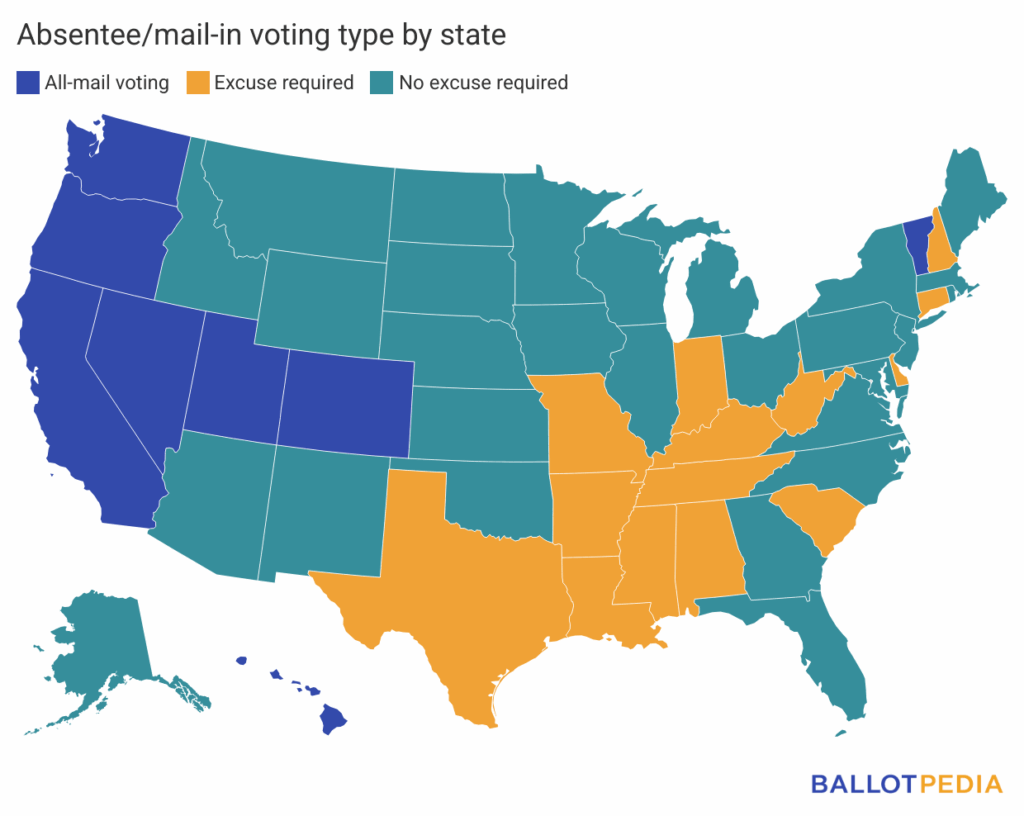

Forty-two states require voters to initiate the process of requesting an absentee/mail-in ballot. Of those, one state, Massachusetts, mails each eligible voter a request form. These 42 states can be divided into two groups: states that require voters to meet specific criteria to vote by mail, and those that don’t.

Fourteen states require voters to provide a valid excuse to vote by mail. Acceptable excuses vary by state but can include illness, disability, or a voter being absent from their polling location on Election Day. Twenty-eight states allow any eligible voter to cast an absentee/mail-in ballot.

Eight states and the District of Columbia have automatic mail-in ballot systems, also known as all-mail voting, where every eligible voter is mailed an absentee/mail-in ballot. While in-person voting is still offered in those states, the primary method of voting is by mail. Vermont uses all-mail voting only in general elections.

Click here for more information on absentee/mail-in voting in each state. Click here for more information on all-mail voting.

We’ve covered where absentee/mail-in voting is available and how those policies can differ across the country. States also vary in how they handle ballots that don’t meet verification requirements.

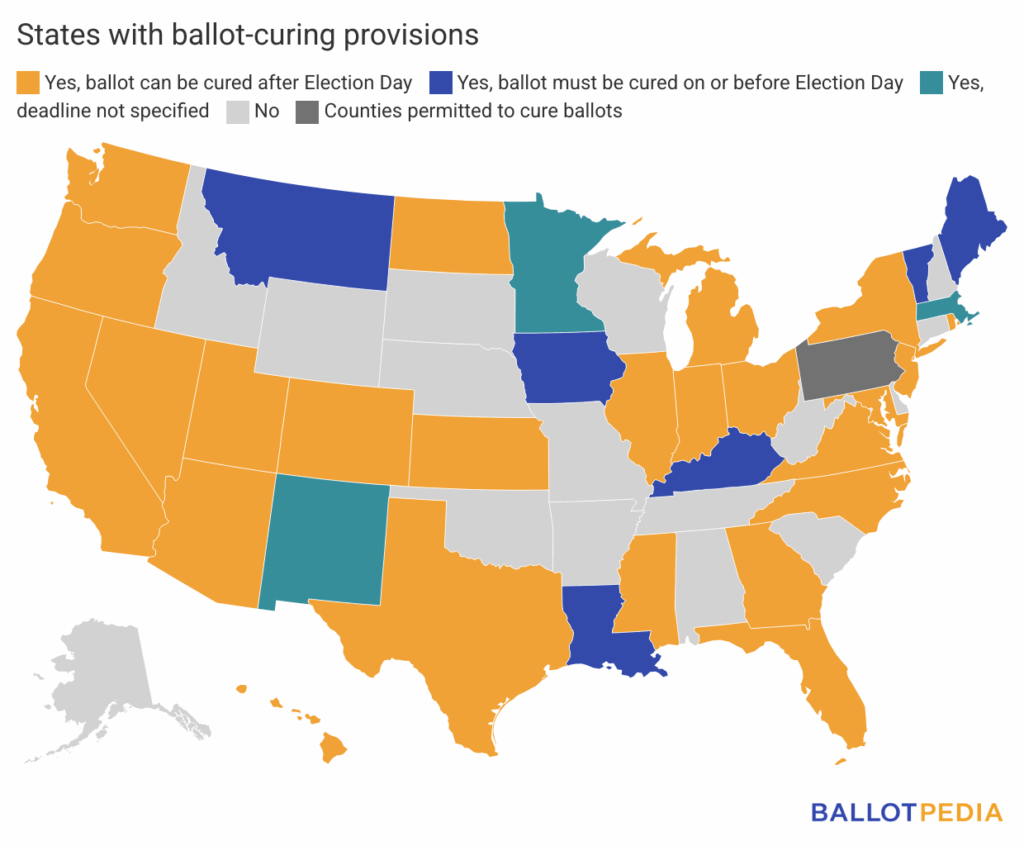

All 50 states require voters to sign their absentee/mail-in ballot return envelopes. In the event of a missing signature or a discrepancy in signature matching, some states require officials to notify voters and allow them to correct signature errors through a process called ballot curing. In states that do not have a ballot curing process, ballots returned without signatures — or, in states that conduct signature matching, with mismatched signatures — are not counted.

Thirty-three states require ballot curing, while Pennsylvania allows counties to cure ballots but does not require it. Thirteen states with a Democratic trifecta, 11 states with Republican trifectas, and nine states with divided governments have ballot curing provisions.

Twenty-four states explicitly allow voters to cure their ballots after Election Day, six states require that curing take place on or before Election Day, and three states don’t specify a set deadline for curing.

In 2025, legislators introduced 48 bills related to curing. Eight bills in six states have become law. Four states adopted five laws related to cure provisions in 2024. Nine states adopted 11 such laws in 2023. Three states adopted four such laws in 2022.

To learn more about legislation related to absentee/mail-in voting and cure provisions, check out Ballotpedia’s Election Administration Legislation Tracker.

Click here to learn about cure provisions for absentee/mail-in ballots in each state.

One election ends, another begins: The 2026 midterm campaigns are already underway

Aside from a few ballots still being counted in some localities, the 2025 election season is in the books. Welcome, Daily Brew readers, to the beginning of the 2026 election season. It’s already well underway in states that have early filing deadlines for their primaries.

What do we already know about next year’s elections? The lion’s share of public and media attention will be focused on the congressional midterm elections. The outcome of those elections will determine which party controls one or both chambers of Congress and what that will mean for the Trump administration’s policy initiatives through the remainder of the president’s term in office.

What we also know is that the congressional midterms will only represent a fraction of the candidates running for office next year.

Arguably, the most important elections will be for the tens of thousands of local offices and candidates that will appear on ballots across the country next year. These races include school board and city council seats, mayoral elections, and elections for state and local judges.

It’s in these elections for thousands of local offices that our daily lives intersect most directly with representative government.

The people we elect to these offices will decide on policies that affect our kids — from what they study every day in class, to when, or if, they can use cellphones at school. It includes county commissioners who might decide whether to locate a data center next to a residential area, or city council members who may vote on rezoning parts of town for higher-density home development. Or perhaps it’ll be a local judge who handles divorce cases, traffic infractions, or probate cases.

Voters entrust local officials with a significant amount of responsibility, legal authority, and tax money. But outside of major cities and large school districts, coverage of these races is often sparse or nonexistent, leaving voters with little or no information about candidates who will make decisions affecting their daily lives.

How is this possible?

One big reason is that there are more than 500,000 local elected officials nationwide. With most serving four-year terms, that could mean approximately 125,000 local elections scattered across the calendar each year — a staggering number of races for news organizations to monitor and cover.

Getting that information is not easy. One of the services Ballotpedia provides free to every voter is our Sample Ballot Lookup Tool. To find the candidate data that goes into this online tool, our staff and volunteers gather information from the 7,700 local election websites across the country. Some of these sites are state-of-the-art, with information readily available, while others have incomplete candidate lists, confusing navigation, or outdated designs. That’s the nature of our electoral system — it’s dispersed, locally controlled, and the rules and calendars local officials use to conduct their elections are often more complex than the average voter can imagine.

And there’s one more twist: often, much of this candidate information isn’t available until about two months — or less — before the election.

That means Ballotpedia’s Elections Team has to complete huge volumes of work in a very short time to ensure our own Sample Ballot Lookup Tool can provide voters with the bare minimum of data about local candidates.

Whenever possible, we try to give voters more than just a name, an office, and the date of the election. We aim to provide at least one additional piece of information — like a survey response, endorsements, or campaign themes — that can help us create what we call a robust candidate profile.

And it’s on this front that there are some fascinating and potentially game-changing projects underway — ones that could transform the way endorsements are made and how they are shared with voters. I’ll dive into that topic in next week’s column.

Federal government shutdown now longest in U.S. history

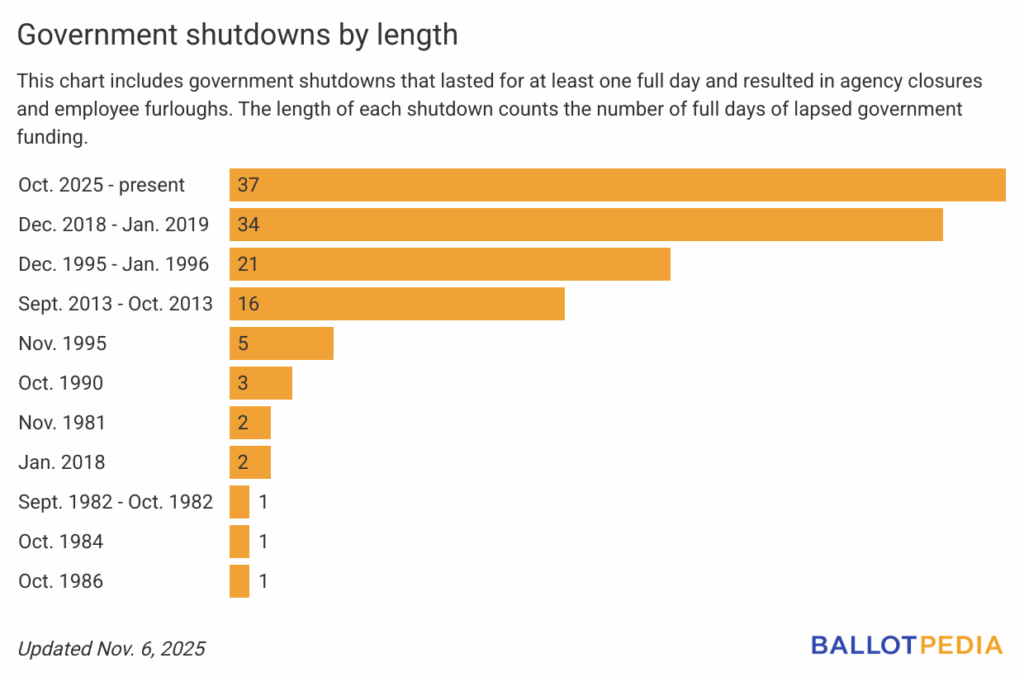

November 4th was the 35th day of the federal government shutdown making it the longest shutdown in U.S. history. It has outlasted the shutdown that ran from December 2018 to January 2019, which lasted 34 full days.

There have been 11 shutdowns in U.S. history that lasted for at least a day and resulted in agency closures and employee furloughs. See the chart below for the length of each shutdown.

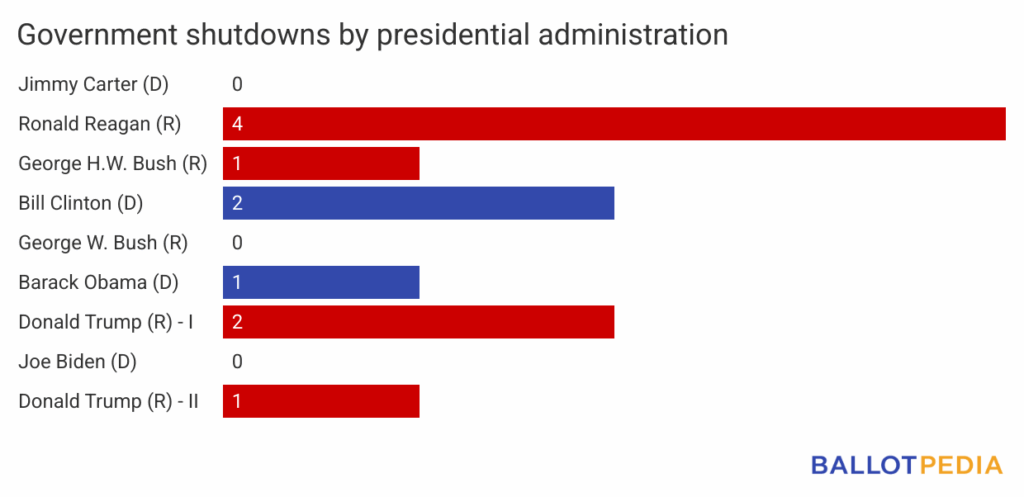

This is the first government shutdown of the second Donald Trump (R) administration. There were two shutdowns during Trump’s first term. The most shutdowns – four – occurred during Ronald Reagan’s (R) two terms between 1981 and 1989.

This is the third government shutdown to begin under a Republican trifecta, with the first two being the two shutdowns during Trump’s first term. The December 2018 - January 2019 shutdown began during a Republican trifecta, but ended under a divided government after the new Congress was sworn in. The other eight shutdowns took place entirely under divided governments.

The current federal shutdown began on Oct. 1 after the Senate did not pass a continuing resolution to fund the government for several weeks. One major sticking point was that Republicans and Democrats disagreed on whether to include the extension of expanded premium tax credits for the ACA marketplace in the continuing resolution. Click here to learn more about the disputes at the center of the shutdown.

A continuing resolution is a type of short-term funding bill that funds the government in lieu of a final budget. Continuing resolutions typically fund the government largely at previous levels, but can change the rate of spending, authorize the continuation of a pre-existing program, or provide funding for the duration of the continuing resolution.

To learn more about each party’s budget goals and the president’s role in reaching an agreement, listen to our Sept. 12 episode of On The Ballot featuring Semafor’s Congressional Bureau Chief Burgess Everett. You can also check out our episode from earlier this year to learn more about what happens when there is a federal government shutdown.

To read more about the government shutdown, click here.